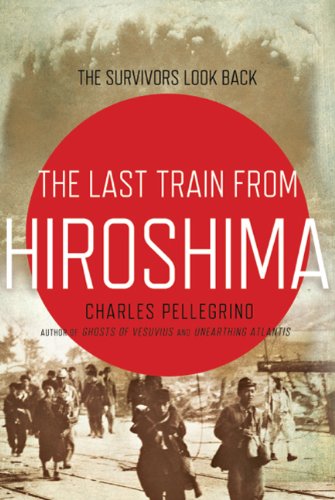

The kerfuffle of the week has been the news that an acclaimed new book, The Last Train from Hiroshima by Charles Pellegrino, had to be withdrawn by its publisher following the revelation that important details in it, including the testimony of a supposed eyewitness source, were apparently fabricated.

As happened in earlier cases of authors doctoring the truth, some readers have raised questions about "quality control" problems in publishing, and asked, don't publishers fact-check their products?

Well, no, actually. A major difference between book and magazine or newspaper publishing is that publishers don't have fact-checkers on staff, and never have. This is not, as some cynics might suppose, because book publishers don't care about accuracy as long as a book sells. It's partly because, unlike those media where advertisers support (or used to) a large editorial staff, book publishing has been a far leaner enterprise (or as some would say, a cottage industry). But a more important reason, I believe, is that in book publishing, unlike journalism, the content has traditionally belonged to the author, not to the house.

This is reflected in book contracts, where copyright is typically retained by the author; more to the point, it's firmly established in publishing culture that you never make editorial changes without an author's consent. As an editor you may lean pretty hard on an author to make revisions you feel are necessary (Gordon Lish's interventions with Raymond Carver being the extreme example)--but ultimately, "the book belongs to the author," and to change it or not is his or her prerogative. With that prerogative goes, inevitably, a greater responsibility for the quality of what you write.

Now, any good publisher wants to produce the best books possible. While we don't have fact-checkers, we have copyeditors who go through manuscripts with a fine-tooth comb, after the editor has already worked with the author to get the book in shape. I have done my own fact-checking from time to time when an author's statement seemed questionable, and the best copyeditors will frequently check sources as well as spelling and punctuation. Furthermore, any manuscript that might raise issues such of defamation or privacy goes through a careful legal review. In the end, though, we have to trust our authors.

I don't take on a work of nonfiction, especially a controversial or even unconventional one, without satisfying myself, perhaps just at gut level, that the author is presenting the truth responsibly. But I have to recognize that I can be fooled. Reading about the case of Charles Pellegrino, who supposedly produced--or at least, said he had--documentation of his bogus souce (who was a real person, but apparently not present at the event he claimed to witness), I suspect I might well have accepted the author's account.

Once we have decided to trust an author, we usually give him or her the benefit of the doubt on matters of fact just as on matters of style or argument. Of course, this leaves us vulnerable. But in book publishers' defense, the impulse to trust the people you work with is a hard one to overcome. Look at the cases of Janet Cooke, Stephen Glass, or Jayson Blair, whose fabrications sailed through the presumably gimlet-eyed fact-checking operations of the Washington Post, New Republic, and New York Times respectively.

(Photo of the Bocca della Verita, or Mouth of Truth, at the Church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin in Rome, via Wikimedia Commons. It's said that if you tell a lie with your hand in the mouth of the sculpture, it will be bitten off. Maybe every publisher needs one of these?)

10 comments:

Thanks for this, Peter. It's a sticky wicket, and it makes a difficult job even harder for the rest of us.

As a ghostwriter who co-authors high profile memoirs, I begin every project with stern words to my client about the importance of telling the truth and the futility of thinking they'll get away with a lie. I do my utmost to shore up the story with media and other corroboration, and if I find that the client has lied, I don't hesitate to slap some mama says upside his or her head. So, yes, as an author, I do feel a huge responsibility to do everything I can to ensure the integrity of the book. But I'm not a journalist; I'm something between a sign language interpreter and the Ghost of Christmas Past. I have a duty to present my client's story as s/he wants it told, and -- as with any book -- my perspective on the material is coming from inside the appendectomy after a while. I appreciate having my feet held to the fire by a vigilant editor and copy editor.

I almost always get that support, but on one occasion several years ago, I went to my editor (and this was at a highbrow house where literary values were much blustered about) with the inconvenient truth that they'd given my client a sizable advance for a hot steamy pile of BS. My editor told me I was "over-parsing" the facts and needed to understand the idea of artistic license. I flew home from NY to find an email telling me I was fired. For reasons I'm not privy to, the book never made it to publication, but at least two other writers were hired and fired after me in an attempt to make that doodoo bird fly.

Maybe the publisher can arguably eschew legal responsibility in the aftermath of this Hiroshima kind of thing, but at the very least, they should be there on the front end, asking the hard questions.

When I blogged about the Hiroshima plot bomb last week, I referred to this post from a year ago that speaks to how these things evolve and who's most deeply hurt by it:

http://boxingoctopus.blogspot.com/2008/12/angels-and-liars-and-another-dark.html

Thanks again for your insightful post.

Dear Peter,

I notice that Charles Pellegrino is a regular associate of James Cameron, who is (still) planning to make a film about Hiroshima. Is part of the problem that the book business is getting more like the movie business – that a "property" is either a blockbuster or a flop, rather than the neat meshing of writer with readership that publishers used to manage so well? The temptation to salt the mine intensifies if the author's prospect is either bestseller or pulp.

Sadly, the Mouth of Truth was also over-billed, being in fact a manhole cover for Rome's main sewer. All the more appropriate, then.

Judith, very good question! I will answer it in my next post.

Joni, thanks for your comment and the link to another thoughtful post. There are always temptations for both authors and publishers to make a story better than it really is. Just as some authors have played fast and loose with the truth, sometimes publishers have been willing to put out books without inquiring into them as closely as they should. The same impulse exists in journalism, which is why there's the *mostly* jocular tag, "Too good to check."

If the publisher you mention initially took a "too good to check" attitude to the "BS" you alerted them to, nonetheless it sounds like some kind of quality control finally kicked in, if the book in question was never released.

Michael, I think it's indisputable that the book business has become more like the movie business--in fact Thomas Whiteside's book THE BLOCKBUSTER COMPLEX was published as far back as 1980 and the trends he spotted have only continued. I can't be sure if that increases the pressure to massage the truth. Authors have been peddling trumped-up stories and sacrificing accuracy to a good yarn since well before blockbuster-itis set in.

A slightly different hypothesis might be that part of the problem is not the analogy of publishing to movies, but the actual overlap between them. Movies, partly because of the needs of the form, are far more likely than books to doctor historical fact. Maybe if Pellegrino has been hanging out with screenwriters, that's where he got the idea that taking a real character and putting him somewhere that he never went, witnessing an event that was dramatically potent (but just didn't happen to happen), was an acceptable strategy.

In fairness to Pellegrino I should note at this point that he claims to have been duped by his faux eyewitness, rather than having fabricated things himself. That claim is undermined by other inaccuracies and apparent fibs in his personal history, but not yet disproven.

Came across this post just today. I'm a scientist, working in genetics/evolution. Checked out Pellegrino's website. It was immediately obvious that Pellegrino (with claims of work on paleontology, antimatter rockets, archeology, etc.) was a total fraud. Any halfway competent scientist would recognize this. So I'm surprised he's gotten away with it this long.

I ended up coming across your post because I've been looking into an author published by Simon and Schuster. I discovered that he plagiarized heavily, and has fabricated as well (the plagiarism has now been widely reported, through the fabrication has only received somewhat minimal press attention so far). I tried contacting Simon and Schuster recently, regarding a series of additional quotations that appear likely fabricated. Given the very specific information I provided, I thought they might do some minimal fact checking. But, at least at this point, stonewalling (i.e. no reply) is the only response I’ve gotten. From a couple of articles I've read today (e.g. about the Goodwin plagiarism case), it seems that Simon and Schuster's typical response in such cases is to circle the wagons.

Eurytemora, I would not necessarily assume S & S is "circling the wagons" if they have not responded to you. They may be doing their own checking; or, to be honest, if the title is not recently published and not selling very actively, making corrections to it may not be a high priority. If a book has already been proven to be fatally flawed, the contract may have been terminated even though copies are still on bookstore shelves. It's usually not possible to withdraw all printed books from the marketplace once they have been distributed. If it's still an active title, you should get a response. (If you don't, find out what editor is responsible for it and contact that person).

Peter,

The title was published only six months ago, and is actively selling. After receiving no response to my initial e-mail, I directly e-mailed the editor responsible for the book, and again received no reply.

I found the following articles online, discussing Simon and Schuster’s handling of plagiarism cases.

http://www.prospect.org/cs/articles?article=heavy_lifting

http://slate.msn.com/id/2127883

Simon & Schuster's track record on charges of plagiarism certainly leaves something to be desired. But since I don't know what title you're speaking of or any of the circumstances, I can't really comment further. If there are errors or copyright infringements in the book you're concerned about, I hope you succeed in getting them addressed.

Post a Comment