For a century, publishing has had (as Shiv Singh noted in a presentation at Digital Book World) a business-to-business orientation. Big publishers' customers were retailers, a few wholesalers, and libraries (mostly sold to by wholesalers again). On the rare occasions when an individual reader ordered a book from the publisher, fulfilling the order was such a hassle that the author actually got a reduced royalty because of all the extra costs incurrred.

True, publishers directed some of their marketing (such as advertising) to consumers, and we tried to reach individual readers with publicity. But even our publicity efforts were largely aimed at a small ring of intermediaries like book reviewers or radio/TV producers. The idea of telling a story about ourselves or our industry to the reading public, or explaining to book buyers why our products cost what they do, wouldn't have occurred to most publishers a few years ago.

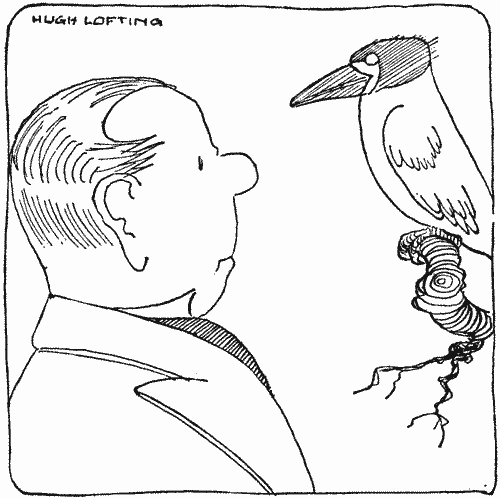

It has at least occurred to some houses by now (and some vertically focused houses and imprints are well along at this), but it's a long way from being fully absorbed by the industry. Publishers are a bit like Dr. Dolittle, slowly learning to "talk to the animals." I'm not being pejorative to either side in that remark. Dr. Dolittle loved the animals--but it took him a while to speak their language. Our readers were out there in all their wonderful variety; we loved them; in our way we took care of them--but we never had a conversation with them.

So, at the same time publishing houses are struggling to master the "disintermediated" marketplace where we can, and must, communicate with end users directly, on top of the old, hard work we have to do of telling people about our titles, we have to explain about how the industry works and why $14.99 for a great new novel is not a ripoff.

All of which gives one pause about the "agency model," where publishers set and enforce their own prices. Just as we have no expertise in talking to readers, we have no expertise in what prices work best for what kinds of titles when. Kassia Krozser notes that "price is an important tool in the arsenal of retailers" who are constantly in conversation with readers, and add their value by getting books into those readers' hands.

Don't get me wrong--I don't believe in rolling over and ceding the job to Amazon or some other behemoth. Just as we have to learn to communicate with readers directly--that is one reason I write this blog--we're going to have to fool around with different pricing schemes and start to figure out for ourselves what works. Doing so will involve a lot more talking to the animals.

(Illustration by Hugh Lofting from Doctor Dolittle in the Moon)

I struggle with this whole pricing thing. I keep reading blogs about how publishers have to sell the value that books provide to their customers. I think customers all ready know the value add stuff. I think people will pay what they think something is worth. People decide the price. I don't think you can educate the masses to pay more. If this worked, then I would imagine that everyone would just raise their prices and tell everyone that the new price is really the right price.

ReplyDeleteI have hard enough time with the $9.99 price since it's higher than most paperbacks. If I buy used, then it's more than twice what I would pay. I'm sure I'm not the only one who thinks this way. I would expect more downward pressure on eBook prices in the future. Now, if we weren't in a recession, then I would think people would be more flexible with pricing. This whole thing is just bad PR, bad timing, and a bunch of angry customers.

Another challenge is trying to convince folks about value on backlist titles, where the costs were spent years ago. I'm curious how that pricing is going to work. With eBooks, a book should never go "out of print."