One group of commenters asks: Who needs publishers? In a digital marketplace authors can readily reach readers directly. Sure, editing is important but, wrote one, “what’s to stop authors from forming consortiums that hire editors?” Instead of settling for a big publisher’s split of royalties, you could distribute the book yourself and keep 100 percent of the profits, or use a service like Smashwords that offers an 85 percent share. This commenter continued, “Right now the business model is that writers are the suppliers of publishers. But it is conceivable that it could become the other way around.”

Another group sticks up for publishers. In defense of Random House’s claim to control e-book rights, these commenters noted that “Books are words in a precise order and meant to be read,” and ask why an e-book is any different. They also point out “the amount of time, effort and money [involved in] making what goes between the two covers of a traditional book.” They ask, not unreasonably, shouldn’t the publisher be entitled to a significant share of income from an e-book whose value is enhanced by the careful editing, copyediting, proofreading, and so on that go into it?

Both groups have legitimate points to make. The book business looks from one perspective like publishers “buy” content from authors and then resell it. But from another perspective, we’re providing a service—enabling the author to reach readers (and collect money for his content). Around Bloomsbury we sometimes say “the author is our customer.” In a sense we are selling the services of editing, design, printing, marketing, distribution and so on. Could a group of authors do the same things themselves? Yes. Of course, then in effect they’d become….publishers. An authors’ co-op might produce more money for writers than a conventional publishing contract, but I don’t know if it would make either writing or publishing radically more lucrative.

As old hands in the business like to say, “If you want to make small fortune in publishing, start with a large one.”

Much ink and many pixels have been spilled on the Random House e-rights issue discussed here last week, and I don’t think I’ll wade into that still-unsettled question again now. I would observe here that although I raised questions about Random’s position on backlist contracts, I agree with them, and most every other publisher, that e-book rights should not be separated from print rights.

Reading a book is reading a book, whether the item being read is a hardcover, a Kindle, or a PDF on a laptop. Amazon and other e-vangelists argue that e-book sales are additional to print sales—that e-book lovers wouldn’t be buying print copies if they weren’t reading them on their Kindles. I’m sure that is true for some books and some readers, but to some extent we know e-book sales replace print sales. It’s clearly essential for a publisher to control all versions of a book that their readers might want to buy. That much is widely accepted by both houses and agents, though there is still debate about what royalties should be paid.

I also agree that those who want to chop down publishers’ share of e-book royalties are often neglecting the big picture. Not only do publishers enhance the value of an author’s work by editing, proofreading and performing those other tasks that go into producing the product you find in a bookstore. They perform a range of other functions that contribute materially to that value. And one of the most important things that publishers do to market electronic books is—sell printed books! I’ll talk about this more in a future post.

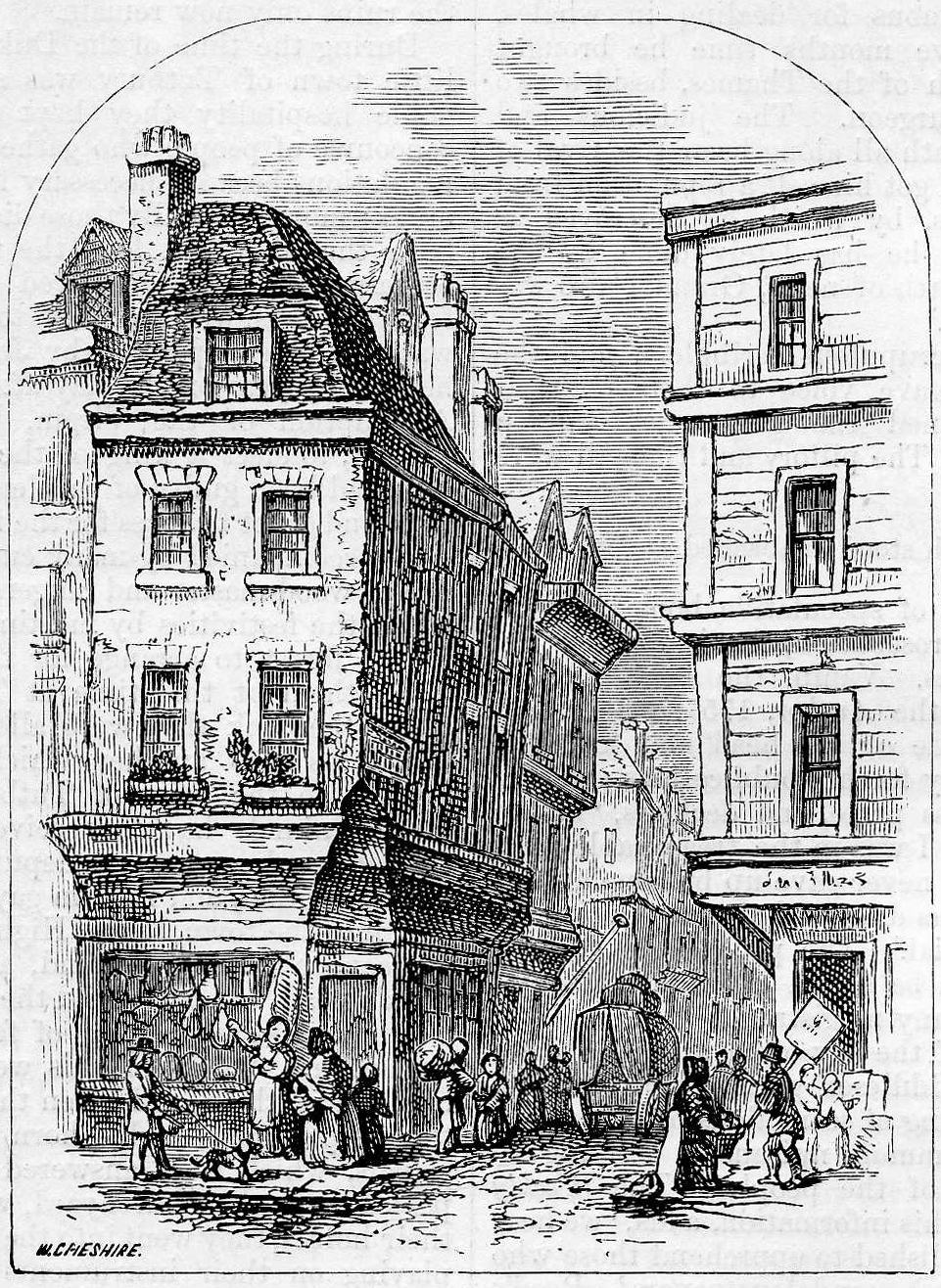

(illustration: Grub Street, later known as Milton Street, from Chambers' Book of Days)