News reports say the President Obama is "soon" going to decide on a strategy for the U.S. in Afghanistan. While Obama and his military advisers ponder whether to continue the American presence there, and on what terms, there has been inevitably much discussion of Vietnam and the missteps we made there five decades ago. Evidently a few recent books about Vietnam are being avidly read around the Pentagon and West Wing, including Lessons in Disaster by Gordon Goldstein and A Better War by Lewis Sorley.

I have a better suggestion: Jungle of Snakes by James Arnold. Arnold looks not only at Vietnam, but three other counterinsurgency wars of the 20th century: the U.S. in the Phillippines at the beginning of the century; the British in Malaysia following World War II; the French in Algeria; and the U.S. in Vietnam. The first two of these were successful campaigns that defeated insurgencies, the second two were failures.

As many observers have pointed out, Afghanistan is different from Vietnam in many ways. Nor is it exactly like the other conflicts I just mentioned. But all counterinsurgencies have features in common, as Arnold's work makes clear--for instance, any counterinsurgency must begin by assuring security of the civilian population; the success of any campaign depends on quality intelligence; and no counterinsurgency can succeed in the absence of a central government that earns the population's trust.

Rather than obsessing over Vietnam--admittedly, the most painful wound in the nation's military psyche--our strategists might profitably expand their data pool by considering what has worked, or failed to work, in other settings as well. Arnold, a veteran military historian, crisply and dramatically conveys what it was like for American boys plunked down in a Phillippine jungle, or French officers trying to tell friend from foe in Algiers (where, disastrously, they resorted to torture). And he steps back to sort out some key principles that any commander facing outlaws and guerrillas needs to know. I recommend Jungle of Snakes to anyone who wants to understand the kind of "asymmetric conflict" our nation is likely to be involved in for the foreseeable future.

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

How Should an Author Respond to a Bad Review?

The Kerfuffle of the Week in the book reviewing world was the dustup between Mark Danner and George Packer over the latter's mostly negative review of Danner's new book, Stripping Bare the Body, in the New York Times Book Review. Danner responded to Packer with a 1400-word rebuttal, or rather a 1400-word critique of Packer's review and of the Times for assigning it to him in the first place. (Packer than riposted in a shorter answer also published in the TBR.)

I admire both writers' journalism, and not having read Danner's book, I won't try to pick sides in the dispute. I merely want to point out how lucky Danner is to have been given so many column inches to punch back at a review he didn't like! Usually trying to rebut bad reviews is a losing game. Few publications can, or care to, allot much space to an author with a chip on his shoulder (justified or not) about a poor review. As you can imagine, the wronged author typically has a lot to say about what was wrong with his review--then he or she finds his epic fulmination edited down to a 200-word bleat. Making it worse, the reviewing organ gives the original reviewer space for a re-rebuttal that is often longer than the author's critique.

This is one reason why I often suggest to authors that they ignore bad reviews. It's better to be philosophical and figure that any publicity is good publicity. (I have come to believe this is usually true, with some ghastly exceptions.) But even if you believe that your book has been misrepresented and the record must be set straight, the result of the tit-for-tat-for-tit exchange rarely comports with your sense of justice.

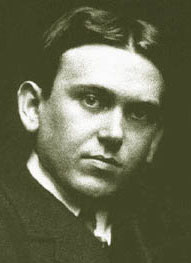

My advice to authors is to take the approach of one notoriously controversial writer, who--at least according to literary legend--had a pre-printed postcard that he used to reply to readers who wrote in to excoriate him for a some column or article. It read, entirely, as follows:

Dear Sir or Madam,

You may be right.

Sincerely, H. L. Mencken.

I admire both writers' journalism, and not having read Danner's book, I won't try to pick sides in the dispute. I merely want to point out how lucky Danner is to have been given so many column inches to punch back at a review he didn't like! Usually trying to rebut bad reviews is a losing game. Few publications can, or care to, allot much space to an author with a chip on his shoulder (justified or not) about a poor review. As you can imagine, the wronged author typically has a lot to say about what was wrong with his review--then he or she finds his epic fulmination edited down to a 200-word bleat. Making it worse, the reviewing organ gives the original reviewer space for a re-rebuttal that is often longer than the author's critique.

This is one reason why I often suggest to authors that they ignore bad reviews. It's better to be philosophical and figure that any publicity is good publicity. (I have come to believe this is usually true, with some ghastly exceptions.) But even if you believe that your book has been misrepresented and the record must be set straight, the result of the tit-for-tat-for-tit exchange rarely comports with your sense of justice.

My advice to authors is to take the approach of one notoriously controversial writer, who--at least according to literary legend--had a pre-printed postcard that he used to reply to readers who wrote in to excoriate him for a some column or article. It read, entirely, as follows:

Dear Sir or Madam,

You may be right.

Sincerely, H. L. Mencken.